you can't make something that's personal to you without it probably hurting someone - that's the human experience." "Boyfriend dungeon proved that there's a growing trend of people who are pushing hard for people to make works that cater to specifically them, even when they think they're pushing for the greater good and for all works to be more safe. For there to not just be content warnings, but toggles to remove stories and characters and topics from games entirely. For Boyfriend Dungeon to remove a plot-critical character and arc. The line, for a lot of developers, comes when aggrieved players start making demands for queer works to be something they're not. At the same time, it just makes me feel like I'm making something that they'd consider damaging, and I'm afraid of how people will respond to that."įor a lot of us indie teams, it's damned if you do and damned if you don't. "I see the general sentiment that people are tired of queer stories featuring characters going through hardship, and I understand why.

"Boyfriend Dungeon makes it very clear that for a lot of us indie teams, it's damned if you do and damned if you don't," said Unbeatable producer Jeffrey Chiao.

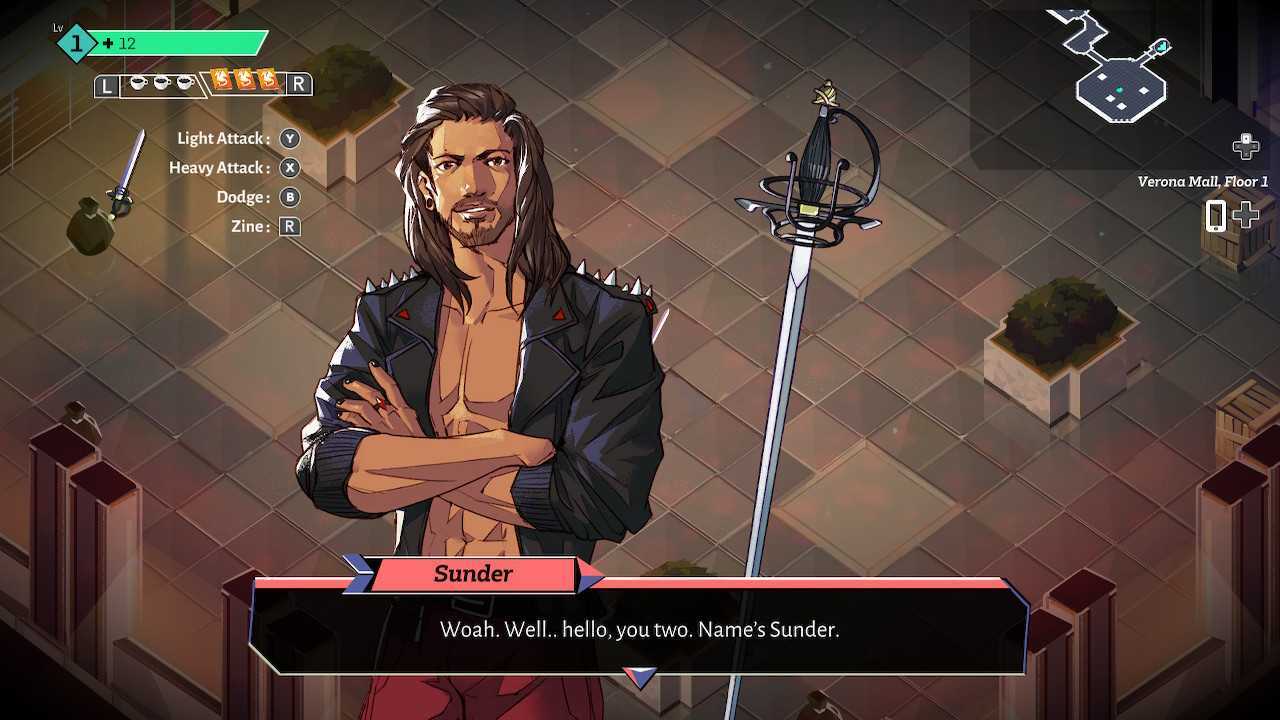

But the simple presence of a touchy subject like stalking saw such strong backlash that it's given plenty of developers pause. Boyfriend Dungeon isn't a heavy game-it's a game about flirting with medieval weaponry, after all-and even took care to launch with content warnings, even if they weren't quite up to scratch. Are we not going to be able to talk about this stuff? Or what is the alternative? Sanitize our work?"ĭevelopers I spoke to shared a common anxiety over tackling these personal themes in games. "I thought about smaller creators that wouldn't be able to take a hit like this, I thought about creators who want to make games about their personal traumas or experiences, that deal with difficult subjects. "The standard is so different from non-queer media, that even if we stay on the subject of stalking, you can click to watch Jessica Jones or You on Netflix and there's no content warning at all. That accessibility ends up holding smaller, marginalised devs to impossible levels of scrutiny, the Kitfox developer explained. When you're using a personal Twitter account for self-promotion, it's hard to leave those comments at work. Without the PR departments and marketing agencies of bigger studios, queer developers felt they were "more approachable" to aggrieved fans (from all sides of the political spectrum). Independent queer artists and filmmakers have been dealing with similar backlash for decades. This kind of response goes well beyond games, of course. Bisexual developers slammed as biphobic for not conforming to a specific kind of bisexuality. Anecdotes of comments and messages from fans who felt that their representations of marginalised identities weren't "correct" because they didn't map to the commenter's own experience. Many developers I spoke to shared an anxiety over how their particular views of queerness would be met by wider audiences. "For as inclusive as we’re trying to be, at some point we had to say, 'Look, if drag queens really bother you, this isn’t the game for you.'" But drag is a key part of Coats' own view of queerness, one that felt too essential to omit.

Coats tells of a response from a trans fan who was frustrated with the presence of a drag queen in the game's cast - after all, drag has long been conflated with transness in messy, uncomfortable ways. There's value in seeing stories where we just get to exist, without reliving very personal pains over and over again.īut creating honest queer art often means reflecting and unpacking what queerness means to the artist-no matter how messy it may be, or where it may rub against other parts of the community. There are enough tropes out there of queer-coded villains or tragic gay couples that many queer players just want to see themselves represented in safer, more uplifting stories.

Sometimes that leftover anger and pain gets misdirected at the very creators trying to make it better." "While it’s gotten easier, part of the queer experience is working through that trauma to accept who you are. "Existing as a queer person means growing up with trauma and pain," Coats explained.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)